Even as Renuka Thakur showed cricketing promise at a young age, the possibility for her talent finding an appropriate stage had always been minimal. After losing her father, a cricket tragic, at the age of three, her mother Sunita was forced to take a job as a Class IV employee with the local government. Growing up in Parsa village within the small hilly town of Rohru, some 40 km away from Shimla’s city centre, resources were scarce.

That was when, at the age of 13, Renuka’s uncle persuaded the family to move her to the residential academy started by the Himachal Pradesh Cricket Association (HPCA) in Dharamshala. Looking back 16 years later, for India’s pace spearhead who played a key role in their landmark World Cup triumph this year, the giant leap of faith was evidently a life-changing moment.

“There is nothing I can say that would be enough about the role that the academy played in her life,” Sunita told The Indian Express. “It is thanks to all the work they did with her there that she played for India, and eventually, won the World Cup.”

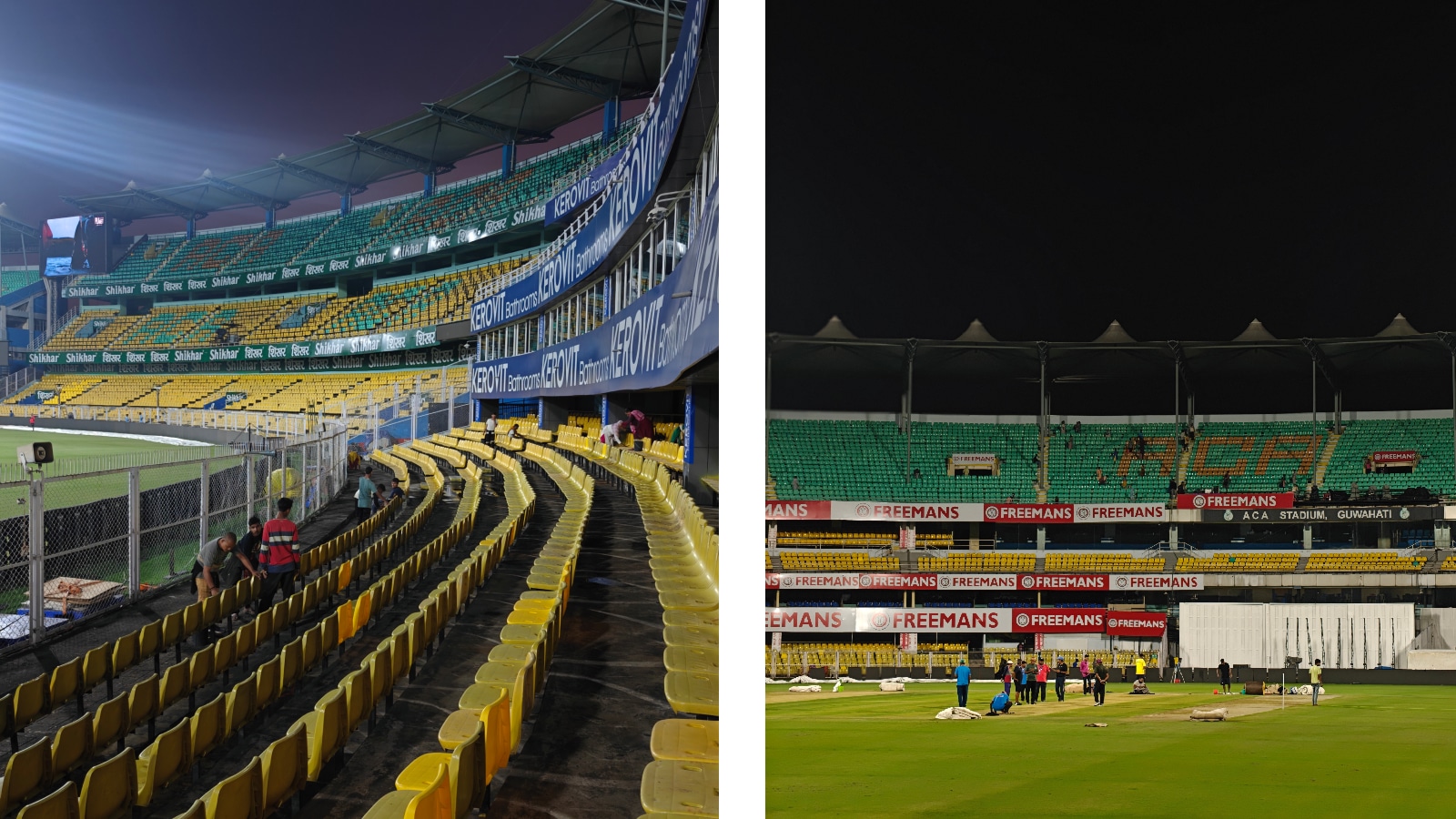

Girls of different age groups train at the HPCA residential academy facilities in Dharamshala. Credit: HPCA

Girls of different age groups train at the HPCA residential academy facilities in Dharamshala. Credit: HPCA

The academy that started in 2009, then a total unicorn – specialised coaching for women’s cricket itself had been hard to come by then, let alone a fully residential set-up – has now produced four international cricketers: Sushma Verma, Tanuja Kanwar, Renuka and Harleen Deol. The latter two were core members of this year’s World Cup-winning squad.

“At that time, who was investing in women’s cricket this much? I certainly would not be an international cricketer without the academy. I had not even thought of playing for my state when I joined,” Verma says.

Today, the academy houses more than 20 players that come from 16 different districts – from Kullu and Shimla to Kinnaur and Mandi – across the Under-16 and Under-19 age groups. It began operations from a local municipal ground, having to share space not only with other sportspersons but also with local melas and herds of cows. It later moved to the picturesque international-grade stadium in Dharamshala, overlooking the Dhauladhar mountain range.

Man behind the mission

From conception to achievements, the academy has been headed by Pawan Sen, a former First-Class cricketer for Himachal who eventually turned coach. For the first few years, Sen would be the de facto in-charge – manager, coach, trainer and medical attendant; making sure the young girls did not pick up serious injuries and also developed some skills, moving them from playing with a tennis ball to tape ball and eventually leather ball.

Story continues below this ad

The initial batch produced two internationals, Verma and Renuka, but before that came to pass, it had been a fledgling set-up, before a catalyst moment came.

For a plucky state association like that of Himachal Pradesh, developing the much-talked-about stadium in Dharamshala marked the beginning of greater ambitions. The association wanted to produce players that represented the national side, and that happened in 2013 when wicketkeeper-batter Verma got picked for India.

“Once Sushma played for India, many more girls came,” Sen says.

The association, too, reinvested by giving them more playing opportunities, adding a trainer and physiotherapist to the set-up, and even being open to importing players from other associations, as was the case when Harleen joined from Chandigarh in 2013. The returns on investments started coming when Harleen and Renuka made their India debuts, and have been sealed with World Cup glory.

Story continues below this ad

So how did a small academy up in the hills produce four internationals, including two World Cup winners? A bit of luck, sure. Also, some untapped potential in the naturally athletic young women who grew up in high altitudes.

Dealing with parental anxieties, especially for some who come from small towns and whose parents are not quite sure about a career in sports, seems to be a key feature.

“I was scared, of course. But I would get to speak to Renuka once a week in those days and every time she sounded happier,” Sunita remembers. “They took care of everything, from food and nutrition to training. They even made sure she went to school. It felt like she grew up with the family only.”

A different way

Another was the added sensitivity in acknowledging that women cricketers need to be dealt with differently from the male players. It’s one thing to produce grounds, give equipment, and lease hostels. It proved to be another to manage the athletes.

Story continues below this ad

“We had to understand this and change our attitudes. Kids can be very emotional, and girls face pressures of all kinds, in their own homes and outside. It can be really tough, and without understanding this, you won’t be able to make them champion players,” Veena Pandey, the academy’s physical trainer, said, adding that safety had always been a priority in the set-up.

Girls of different age groups train at the HPCA residential academy facilities in Dharamshala. Credit: HPCA

Girls of different age groups train at the HPCA residential academy facilities in Dharamshala. Credit: HPCA

It is a problem not unique to cricket or Himachal, “but to all women’s sports in India,” Verma says.

Sen, however, believes it is tougher now than it was a decade ago to run the academy. It may be a bit of recency bias; they have not produced the same number of top cricketers, many of their best trainees have moved out or started representing Railways (like Renuka) in search of a job, and they have even moved out of the Dharamshala facility to a local cricket ground in Kangra for more playing opportunities.

“With the WPL (Women’s Premier League) coming in, kids are seeking that professional contract before playing for their state, I can’t blame them. But that means parents are far more involved now; earlier they used to just trust us. That is its own challenge,” Sen says.

But he knows things can change again with a flicker. “Two of our girls won the World Cup! It means only more will want to play. That is what we need,” he adds.